History

History of Benedictine University

The history of Benedictine University begins with the Benedictine monks of St. Procopius Abbey in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago in 1887. The Benedictine Order bears the name of St. Benedict, born in 480, who is acknowledged as the father of western monasticism. In 528, he established the famed monastery of Monte Cassino.

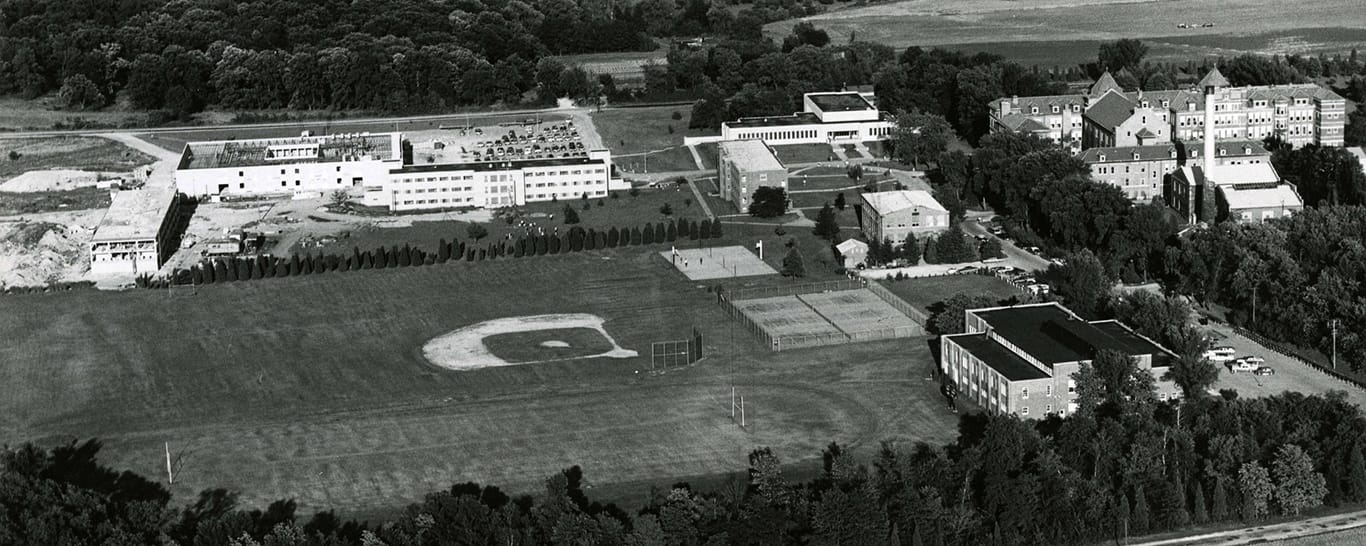

The history of Benedictine University reflects its evolution from a culturally focused institution to a diverse, coeducational university. The first building on the Lisle campus was dedicated in September 1901. That building was expanded into the 1920s, with new buildings added in 1950. The University was originally founded to educate men of Czech and Slovak descent, and in the early years most of the students were from those ethnic groups. The University became coeducational in 1968.

Buildings & Facilities

Recognizing the social, economic and building changes taking place around the University community (which in its earliest days had a significant agricultural character), the University added necessary buildings and facilities to accommodate the needs of contemporary students including residence halls, independent living apartments, a fitness center and state-of-the-art athletic fields.

The University added the Kindlon Hall of Learning and the Birck Hall of Science in 2001 and the Neff Alumni Center in 2012, and in 2015, Benedictine unveiled the four-story, 125,000-square-foot Daniel L. Goodwin Hall of Business, which features an innovative Bloomberg Trading Lab and a 600-seat auditorium. These developments represent a continued investment in modern facilities while honoring the history of Benedictine University, which is reflected in the design and purpose of its growing campus. A renovated quad area, which includes landscaped walkways, gothic-style lighting and rain gardens, connects the front entrance of Goodwin Hall with other key academic, enrollment and student life buildings.

The University gained national and international recognition through major partnerships. In 2003, Benedictine University and Springfield College in Illinois partnered to bring Benedictine programs and services to the state capital.

In 2004, Benedictine collaborated with Shenyang University of Technology and Shenyang Jianzhu University in China to bring Master of Business Administration and Master of Science in Management Information Systems programs overseas where there is a great demand for American business programs. Also in 2004, the University partnered with the Village of Lisle to construct the Village of Lisle-Benedictine University Sports Complex, a multi-purpose facility featuring lighted athletic fields with a nine-lane track.

Benedictine’s Margaret and Harold Moser Center opened in Naperville in 2006 to serve adult and graduate students, and later became the National Moser Center for Adult Learning. Meanwhile, Benedictine became the first Catholic University in Arizona when it established a branch campus in Mesa and opened its doors to students in the fall of 2013.

In 2016, Benedictine rebranded the Moser Center into the School of Graduate, Adult and Professional Education with degree programs offered in business, education and health care. Classes met on campus (Lisle, Springfield or Mesa), off campus at work-based sites (central and northern Illinois, and southwestern Arizona) and online in 43 states.

Today, undergraduate enrollment has grown to more than 3,300 and total enrollment is nearly 10,000. The University offers 56 undergraduate and 19 graduate programs. Most Benedictine students are from the Chicago area and Illinois, although 50 states and more than 15 foreign countries are represented—a testament to how the history of Benedictine University has shaped it into a diverse and globally connected institution.

The Benedictine Order

The history of Benedictine University is deeply rooted in the legacy of the Benedictine Order, named after St. Benedict, born in 480 and widely regarded as the father of Western monasticism. In 528 he established the famed monastery of Montecassino. In the middle ages, Benedictine monasteries expanded all over Europe, preserving ancient learning and written works by hand copying them in their scriptoria prior to the advent of printing with moveable type as invented by Johannes Gutenberg.

Benedictine University belongs to the Association of Benedictine Colleges and Universities, an organization that promotes the Benedictine traditions of education and hospitality.

The Association of Benedictine Colleges and Universities (ABCU)

- The Catholic intellectual tradition includes:

- A commitment to the continuity between faith and reason.

- A respect for the cumulative wisdom of the past.

- An anti-elitist bent.

- Attention to the community dimension of all human behavior.

- A Concern for the integration of goals and objectives.

- A keen awareness of the sacramental principle

- The Social Teaching of the Catholic Church

- The Catholic Church’s social teaching is a rich treasure of wisdom about building a just society and living lives of holiness amidst the challenges of modern society. Modern Catholic social teaching has been articulated through a tradition of papal, conciliar, and episcopal documents, the depth and richness of this tradition can be understood best through a reading of these documents. In our brief reflections here, we highlight several of the themes that are at the heart of the Catholic social tradition.

- “The Life and Dignity of the Human Person.” The Catholic Church proclaims that human life is sacred and that the dignity of the human person is the foundation of a moral vision of society. Every person is precious, people are more important than things, and that the measure of every institution is whether it threatens or enhances the life and dignity of the human person.

- “Call to Family, Community, and Participation.” The person is not only sacred but also social. How we organize society—in economics and politics, in law and policy—directly affects human dignity and the capacity of individuals to grow in community. We believe people have the right and duty to participate in society, seeking together the common good and well-being of all, especially the poor and vulnerable.

- “Rights and Responsibilities.” The Catholic tradition teaches that human dignity can be protected and a healthy community can be achieved only if human rights are protected and responsibilities are met. Therefore, every person has a fundamental right to life and a right to those things required for human decency. Corresponding to these rights are duties and responsibilities—to one another, to our families, and to the larger society.

- “Option for the Poor and Vulnerable.” A basic moral test is how our most vulnerable members are fairing. In a society marred by deepening divisions between rich and poor, our tradition recalls the story of the Last Judgment (Matthew 25:31-46) and instructs us to put the needs of the poor and vulnerable first.

- “The Dignity of Work and the Rights of Workers.” The economy must serve people, not the other way around. Work is more than a way to make a living; it is a form of continuing participation in God’s creation. The dignity of work is to be protected; then the basic rights of workers must be respected—the right to productive work, to decent and fair wages, to the organization and joining of unions, to private property, and to economic initiative.

- “Solidarity.” We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences. We are our brothers and sisters keepers, whatever they may be. Loving our neighbor has global dimensions in a shrinking world. At the core of the virtue of solidarity is the pursuit of justice and peace. Pope Paul VI taught that if you want peace, work for justice! The Gospel calls us to be peacemakers. Our love for our sisters and brothers demands that we promote peace in a world surrounded by violence and conflict.

- “Care for God’s Creation.” We show our respect for the Creator by our stewardship of creation. Care for the earth is not just an Earth Day slogan, it is a requirement of our faith. We are called to protect people and the planet, living our faith in relationship with all God’s creation. This environmental challenge has fundamental moral and ethical dimensions that cannot be ignored.

- This summary should be a starting point for understanding Catholic social teaching. A full understanding can only be achieved by reading the papal, conciliar, and episcopal documents that make up this rich tradition. Copyright 2005, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

- The Catholic Church’s social teaching is a rich treasure of wisdom about building a just society and living lives of holiness amidst the challenges of modern society. Modern Catholic social teaching has been articulated through a tradition of papal, conciliar, and episcopal documents, the depth and richness of this tradition can be understood best through a reading of these documents. In our brief reflections here, we highlight several of the themes that are at the heart of the Catholic social tradition.

- The principles of wisdom in the Rule of St. Benedict

- Wisdom has to do with such things as understanding and judgment. Wisdom is cultivated in community. The guiding idea of Benedictine monasticism is that by coming together—living, praying, working and studying together—we can better grow in wisdom.

- Wisdom—understanding and judging—is a function of how one lives. We tend to assume the relationship between knowing and living—between what one knows and how one lives. This is unidirectional and that direction is from knowing to living, from theory to practice.

- Wisdom flows from how we live. The Benedictine monastic tradition recognizes that knowing, understanding, and wisdom flow from the way we live. Practices of charity, regular prayer, Lectio Divina, obedience, humility, and hospitality may yield understanding.

- Wisdom has to do with the interplay of knowing and living; it is a matter of character and virtue, and the Benedictine tradition manifests this in particular ways.

- Adapted from William J. Cahoy’s paper “Benedictine Wisdom and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition,” June 28, 2006.

- Benedictine Colleges and Universities in North America

- Saint Peter’s College (Muenster, Saskatchewan, Canada)

- Saint Leo University (St. Leo, Florida)

- Benedictine University (Lisle, Illinois)

- Benedictine College (Atchison, Kansas)

- Saint John’s University (Collegeville, Minnesota)

- College of Saint Scholastica (Duluth, Minnesota)

- College of Saint Benedict (Saint Joseph, Minnesota)

- Saint Anselm College (Manchester, New Hampshire)

- Belmont Abbey College (Belmont, North Carolina)

- University of Mary (Bismarck, North Dakota)

- Saint Vincent College (Latrobe, Pennsylvania)

- Mount Marty College (Yankton, South Dakota)

- Saint Martin’s University (Lacey, Washington)